States Rethink Reading

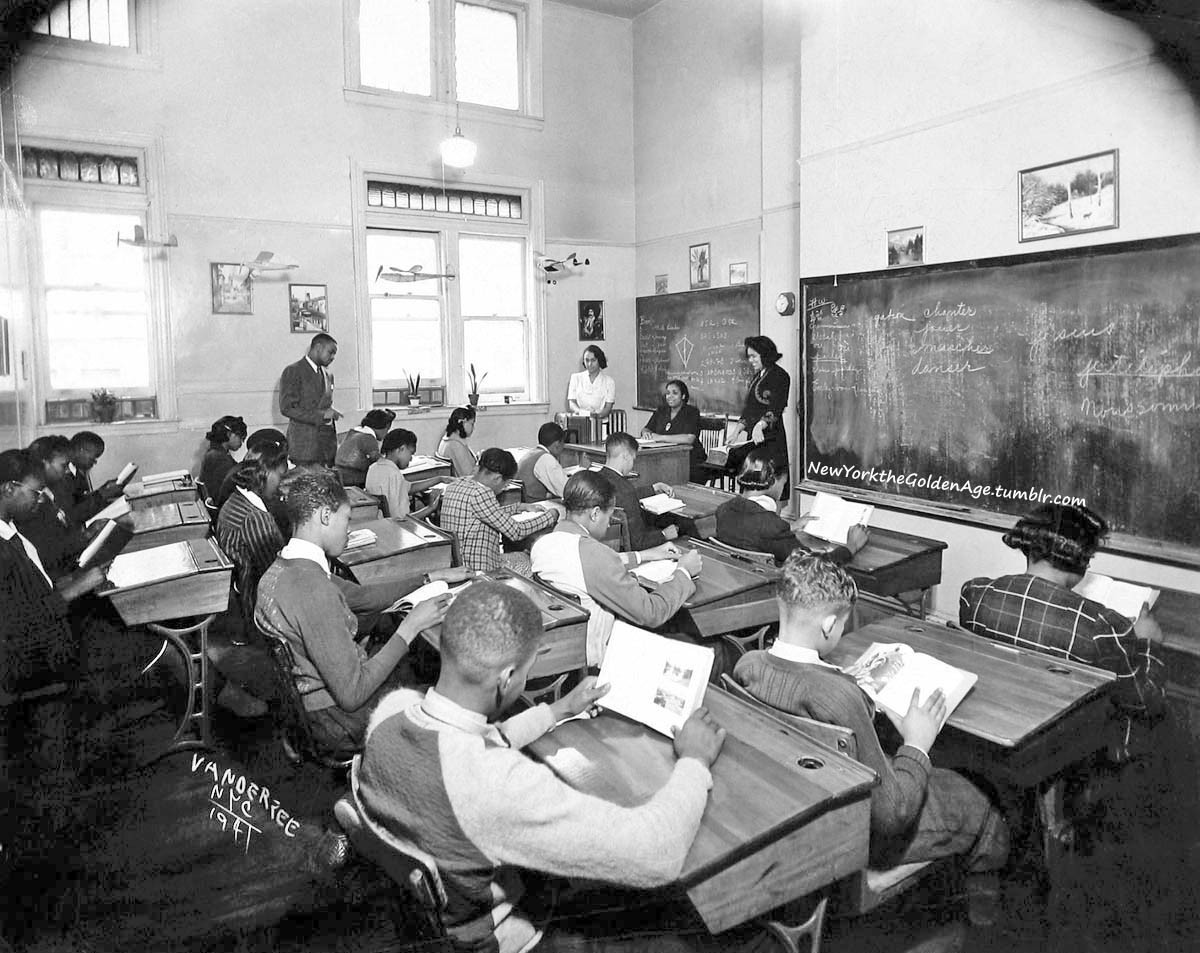

Dozens of cities and states across America are overhauling the way their schools teach reading — attempting to close gaps exacerbated by the pandemic.

Why it matters: Nearly 40% of U.S. fourth graders are below the basic proficiency level for reading, according to a standard national exam.

By the numbers: 37 states and D.C. have passed laws or enacted policies changing up the way reading is taught — pursuing new methods that are backed up by studies.

Zoom out: Reading curriculums in America’s schools haven’t kept up with decades of science and research into how kids learn.

Many districts have long used an approach dubbed “balanced literacy,” which directs teachers to read aloud to kids, inspire a love of books, and teach strategies like guessing words based on pictures or memorizing them.

The new approach, called “the science of reading,” teaches it much more explicitly. It relies on methods that have evidence demonstrating their efficacy, and stresses some key pillars including vocabulary, comprehension and phonics.

Between the lines: The ability to understand language and stories develops naturally in kids, just like walking and talking, but reading does not, says Tiffany Hogan, director of the the Speech and Language Literacy Lab at MGH Institute in Boston.

So the balanced literacy approach, which relies on kids’ intuition to pick up reading, only works for some students.

Studies have shown that phonics-based instruction, however, is effective at raising test scores across the board.

That doesn’t mean teachers should abandon stories and take a sterile approach to teaching literacy, says Hogan. Instead, explicit instruction on how to read words and inspiring a love for books should come together, she says.

How we got here: The reading debate had a breakout moment due to the collision of a number of trends over the last few years, The New York Times reports.

Many parents — home with their kids for the first time during the pandemic — noticed problems with their reading and started a grassroots movement to convince lawmakers and educators to make changes, Hogan said. “The fire was burning, and that threw on the gasoline.”

A podcast from Emily Hanford of American Public Media that dove into the war between teaching methods — and zoomed in on the students who were falling through the cracks — got millions of listens and spread awareness of the issue.

And some early adopters of the new methods saw stunning results.

Zoom in: Mississippi climbed from 49th out of 50 states for fourth-grade reading proficiency in 2013 to 21st in 2022.

State legislators and educators tried a number of strategies, including screening kids for literacy, hiring literacy coaches for teachers, and emphasizing phonics.

“After Mississippi, other states started paying attention,” Hogan said.

Reality check: Most states are rethinking reading, but the progress could take years or decades.

The system is populated with educators who were taught entirely different methods, and “the resistance is real,” said Mark Seidenberg, a psychologist at the University of Wisconsin.

And teachers across the country are being asked to embrace a great deal of change when burnout levels are high and many are leaving the profession.

On top of that, even those who are open to new methods will have to go back to school to get up to speed per their states’ new laws.

“There’s the question of ‘Will these professional development programs and trainings be good enough?'” Seidenberg said.

What to watch: The reading movement has thus far focused on elementary school students and preventing problems in their futures, Hogan says. Next, districts will have to grapple with achievement gaps in middle and high school.

Just 31% of eighth graders and 37% of twelfth graders are at or above basic proficiency. “As students get older, reading ability is a foregone conclusion,” says Hogan. “And it shouldn’t be.”